Temperature swings cause jellyfish blooms and less Polar cod

Jellyfish peaks occur more frequently than before in the Barents Sea. Photo: Erling Svensen / Thomas de Lange Wenneck / IMR

Published: 05.05.2025

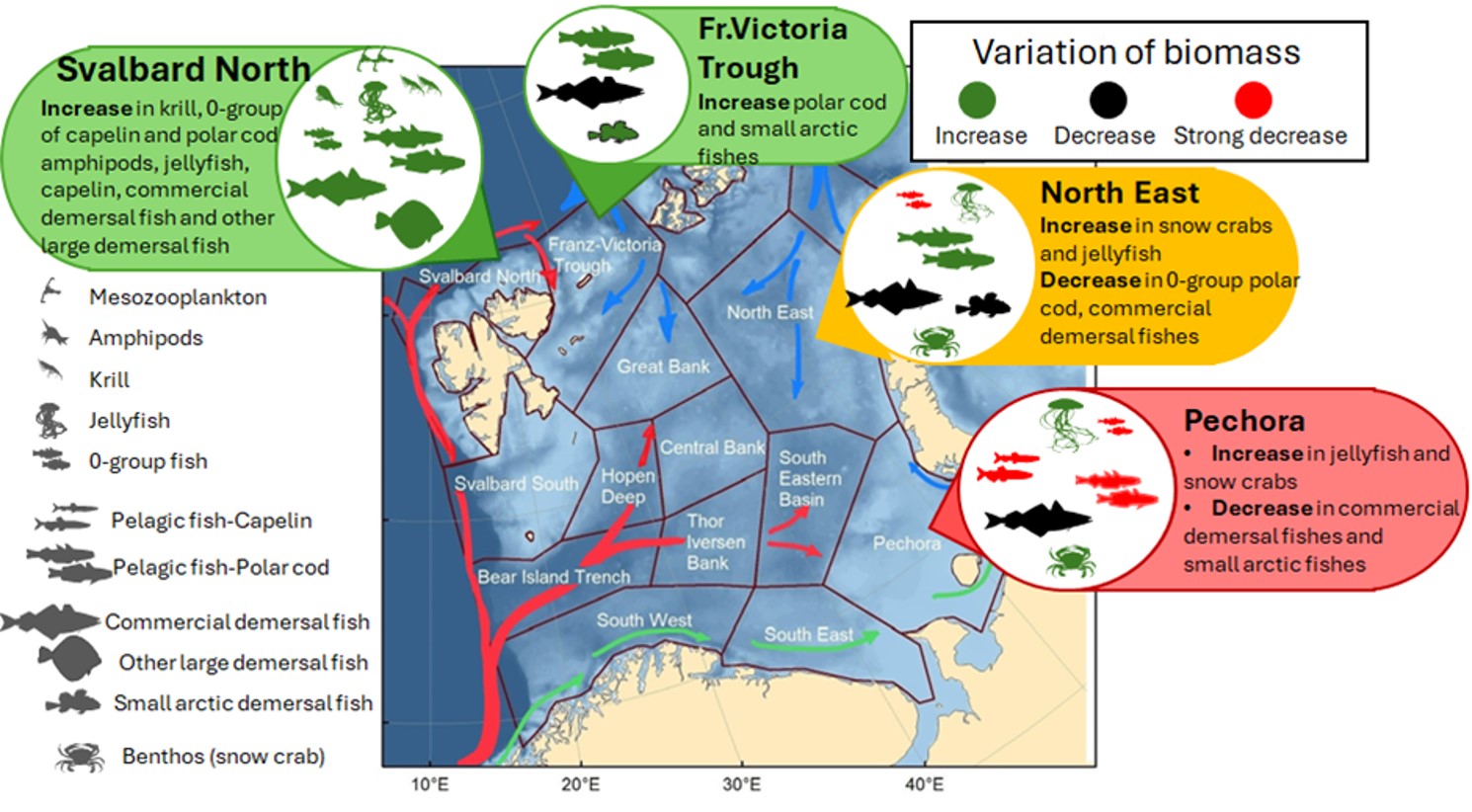

Since 2005, many species of zooplankton, fish, and benthic animals have increased significantly in number in the northwest Barents Sea.

In the southeast Barents Sea, most fish species have decreased in number, while jellyfish—especially lion’s mane jellyfish—and snow crab have increased considerably.

Juveniles of commercially important fish species have spread over larger areas of the Barents Sea: cod and haddock during a particularly warm period, and capelin when the sea cooled down again.

Jellyfish have occupied larger areas and jellyfish blooms have become more frequent —from once a decade to several: 2014, 2017, 2019, and 2022.

Reduced distribution of Polar cod

The geographical distribution of Polar cod in the Barents Sea has been significantly reduced since 2005. The species is now mainly found in the northern Barents Sea.

After a particularly warm period, Arctic small fishes have returned to northern areas.

All these findings are from a comprehensive study of life in the Barents Sea from 2005 to 2022. The results have just been published in Nature Scientific Reports.

Temperature changes in waves

The Arctic is warming almost four times faster than the global average, and it is in the Barents Sea that temperature change is greatest.

The warming does not occur in a smooth, linear pattern.

“On top of an underlying warming trend, there is a period that is very warm, followed by relative cooling,” says marine ecologist Elena Eriksen, the study's lead author.

Three phases over 18 years

The Barents Sea warming from 2005 to 2022 can be divided into three distinct temperature phases:

- 2005-2011: Lower temperatures than the average for the entire period.

- 2012-2016: A very warm period.

- 2017-2022: Somewhat cooler than the previous period.

“We were interested in how the living Barents Sea responds to climate change,” says Eriksen, adding, “The changes in the living Barents Sea were greatest in areas with largest change in oceanographical conditions.”

Best climate adaptation in the northwest

Life in the northwest Barents Sea, near Svalbard, showed the greatest degree of adaptation to climate change.

“Here, there was a substantial increase in biomass of both plankton and fish, but a decline in Arctic small fish during the very warm period,” says Eriksen.

When it cooled and ice returned, the Arctic species increased again.

Where were the small fish?

It is a mystery to the researchers where the small Arctic fish were during the peak of the heat, when they returned after the cooling.

“These are fish that cannot migrate over large distances, so we simply don’t know where they were during the very warm period,” says Eriksen.

Southeast struggles to adapt

In the southeastern Barents Sea, the ecosystem did not adapt to the same extent.

The ice has not returned here, and warming has continued even after 2016. Since the area is so shallow, these changes have affected the region from the surface to the seabed.

The already low biomass of zooplankton and fish in the region has become even lower, while the biomass of jellyfish and crab have increased significantly.

“This is due to high temperatures and increased competition for food. Our findings suggest that jellyfish thrive very well in the southeast,” explains Eriksen.

Researchers now believe we may be witnessing an ecosystem change in the area. This could mean that species that were once here may not return as long as the ice is gone.

No ice, no Polar cod

Neither Polar cod, capelin, nor small Arctic demersal fish species such as the bigeye sculpin have returned to the southern parts of the Barents Sea in the same numbers after the very warm period.

“Our research supports the theory of a spawning collapse for Polar cod in the southeast because sea ice has not returned in winter. The floating eggs are covered by a thin, fragile membrane and can easily be damaged without sea ice to protect them from storms and rough weather,” says Eriksen.

Compared to the 1980s, this represents a significant change. Back then, Polar cod from the southeast dominated the Barents Sea.

“Today, we see no recruitment of Polar cod in the southern area, while Polar cod in the northwest near Svalbard have recently produced a super year class,” says Eriksen.

Although the sea around Svalbard has also warmed, the return of sea ice and cold water is contributing to the recovery of the Arctic ecosystem—at least for now.

Reference

Elena Eriksen et.al. (2025): “The living Barents Sea response to peak-warming and subsequent cooling”. Nature Scientific Reports, 15:13008