Eels only reach puberty at the age of 19

The European eel spawns on the far side of the Atlantic Ocean. The juveniles then head back towards streams and coastal zones in Europe. (Photo: Erlend A. Lorentzen / IMR)

Photo: Erlend Astad Lorentzen / Institute of Marine ResearchPublished: 26.05.2020

At some point in their lives, European eels feel a tingling sensation in their bodies. This is the start of their transformation from a yellow eel into a silver eel. This is when the eels are ready to leave behind the streams and rivers where they have grown up and embark on the long and arduous journey to the Sargasso Sea. There, on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, they will spawn.

But in the River Imsa in Rogaland, the eels are caught on their way out to sea. This has been done since 1975, to help us understand the eel population.

Some eels reach puberty at 30

In the late 1980s, the age of several thousand of these eels was estimated, and the findings of that study have been used as a reference for many assessments. Up until now.

“The methods used then found that the eels were 8-10 years old when they migrated. But scientists realised that they were probably actually older than that”, explains marine scientist Caroline Durif.

And they were right. New analyses performed by Durif and her colleagues on 800 of the same eels found that on average they were twice as old as that.

“The average eel was 19 years old when it migrated to spawn. Some were as old as 30”, she says.

New, more accurate method

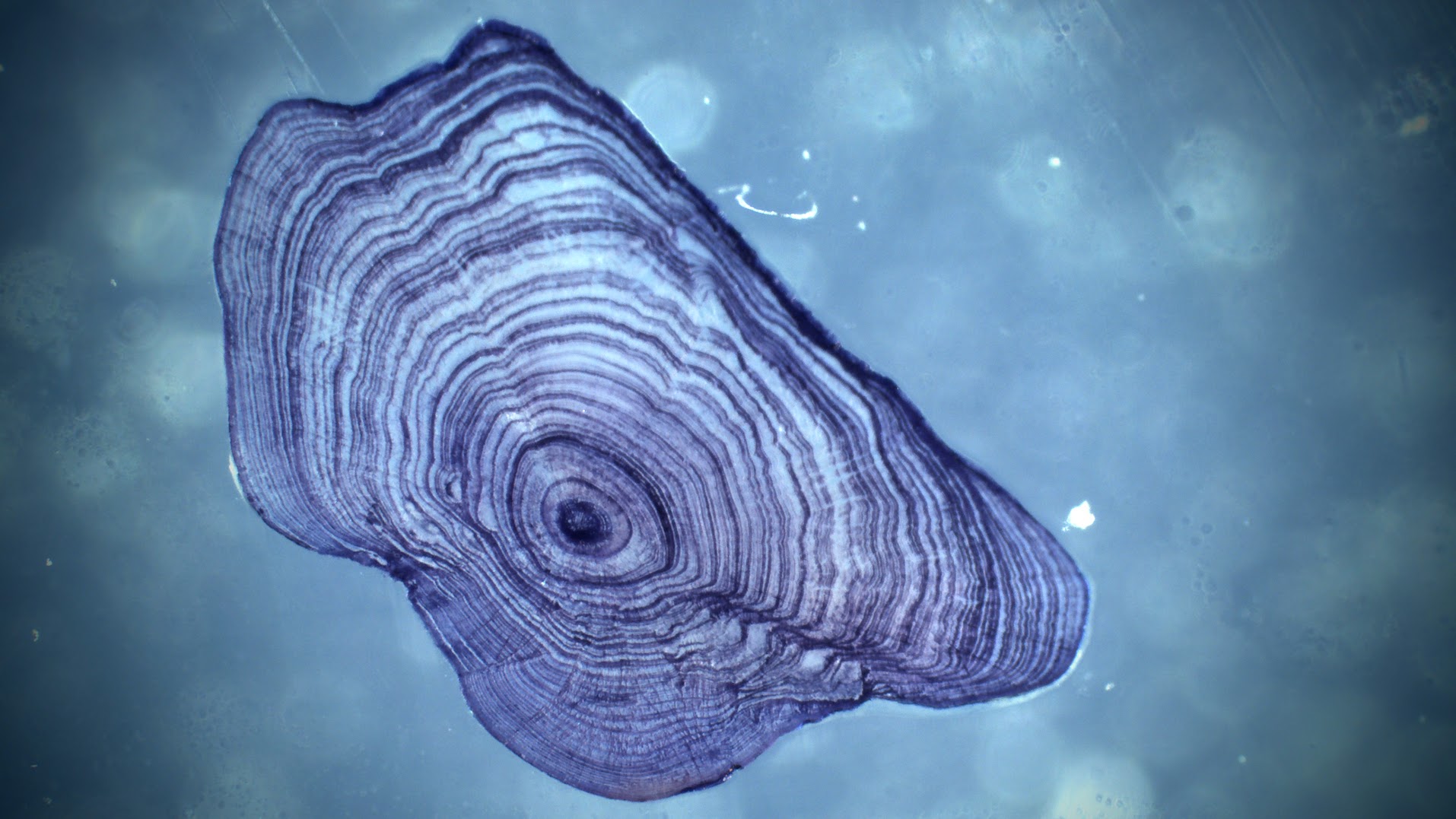

Scientists use otoliths from the eels’ skulls to estimate their age. They can do this because otoliths have annual growth rings.

“In the 1980s, the otoliths were preserved in ethanol and studied under a microscope. When you do that, the annual rings look like grooves”, explains Durif.

“It’s quick and easy, but there is also lots of room for error. Otoliths are uneven and have lots of crinkles, particularly in older fish.

Now Durif and her colleagues have ground down 800 of the otoliths to get clean cross sections and stained them with a special dye. Once that has been done, they look like this:

This makes it far easier to count the annual rings.

“We have also created an index to measure how confident we are in each estimate. That allows us to give less weight to the ones where we’re less certain”, says Durif.

Longer time between generations may be bad news

This surprise about the age of eels may affect our understanding of the whole European eel population. Eels have been struggling since the 1980s, when recruitment started to fall.

“The new results mean that the time between generations is much longer than we previously thought.”

In 2014 the eel was moved from being ‘critically endangered’ to ‘vulnerable’ on the Norwegian red list.

“This was because the eel population was doing slightly better. But the ‘upgrade’ in its classification on the red list was partly based on the number of generations it will take for the population to recover”, says Caroline Durif.

“Now we know that the time between generations is longer, we may have to reassess its category.”

This research project is a collaboration with the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research.

Reference

Durif, Caroline MF, Ola H. Diserud, Odd Terje Sandlund, Eva B. Thorstad, Russell Poole, Knut Bergesen, Rosa H. Escobar‐Lux, Steven Shema, and Leif Asbjørn Vøllestad. “Age of European silver eels during a period of declining abundance in Norway.” Ecology and Evolution (2020). Link: https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.6234