Studying stress in rod and line caught bluefin tuna

Researchers Neil Anders and Michael Breen take samples of pH, temperature, and meat quality in this Atlantic bluefin tuna before it was sent on to the Michelin restaurant Lysverket.

Photo: Pauline Paolantonacci / IMR

Archive photo: After a long day of searching and attempts, HI’s rod-fishing team found this school of bluefin tuna at the very end of the October day.

Photo: Erlend Astad Lorentzen / IMR

Archive photo: Shortly afterward, a fish was hooked on the rubber squid lure.

Photo: Erlend Astad Lorentzen / IMR

Researcher Neil Anders tales a sample for visual inspection.

Photo: Pauline Paolantonacci / IMR

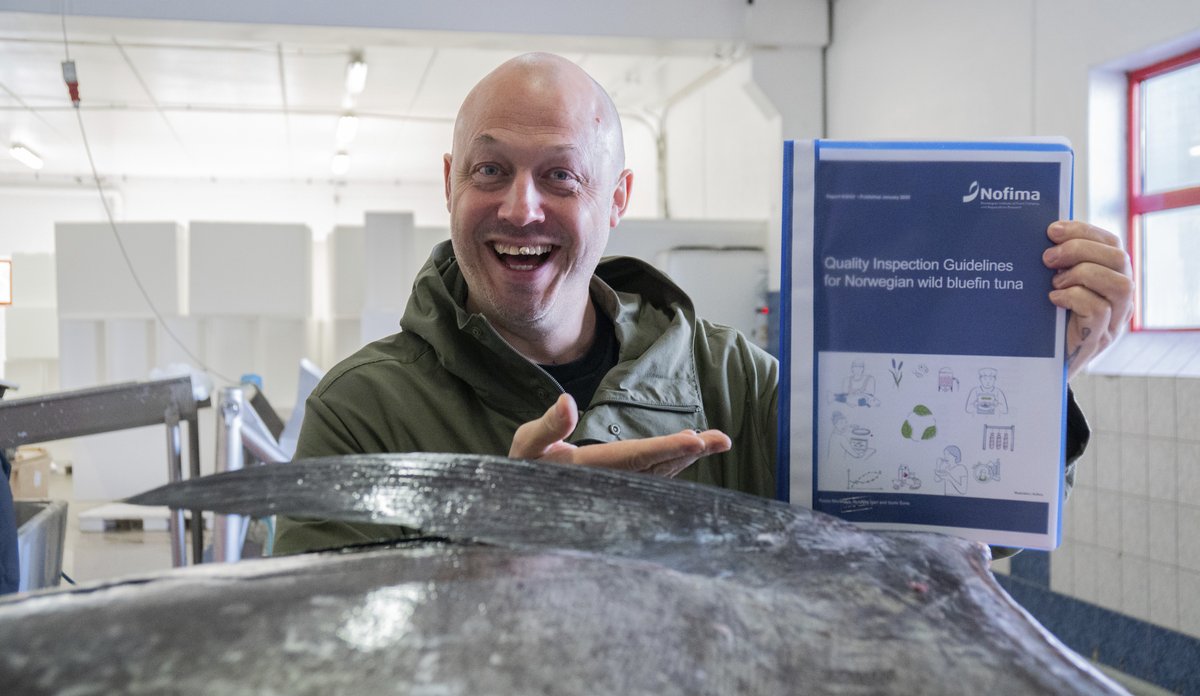

Researchers Martin Wiech, Neil Anders and Michael Breen compare the fillet sample with the newly developed ‘manual’ from Nofima.

Photo: Pauline Paolantonacci / IMR

Lysverket chefs Thibault and Julio are butchering the fish.

Photo: Pauline Paolantonacci / IMR

The fat in Atlantic bluefin tuna has a short shelf life before it can turn rancid. The chefs quickly freeze and vacuum-pack it in smaller pieces before storing it at –60 degrees.

Photo: Pauline Paolantonacci / IMRPublished: 12.11.2025 Updated: 18.11.2025

In the WelTuna project, scientists are studying the condition of bluefin tuna from the moment they strike until they reach the dinner table.

The goal is to maximise fish welfare and meat quality.

Rod and line fishing is a blank slate

“Rod and line fishing has great potential to be a source of sustainably harvested, high-quality bluefin tuna for the lucrative restaurant market. If it is done right, of course”, says Michael Breen, the project manager for WelTuna.

The researchers are documenting everything from capture, including the tuna’s behaviour during the fight, through to the chemical composition of the meat before and after slaughter and the slaughter method. The aim is to establish best practice.

“These fish are enormous, but they are also delicate, since their meat can easily be spoiled. Quick and proper handling is important – both during and after capture”, says Breen.

Tuna dive straight down after striking

Rod and line fishing for tuna is done from fast, small boats. Typically, fishers look for feeding bluefin tuna, and then troll over the school with artificial squid lures.

If you are lucky, a 300-kilo fish suddenly shoots up to the surface and swallows the hook.

That is when the show starts.

“The bluefin tuna quickly dives straight down – often over one hundred metres”, says Breen.

Land the fish quickly

“This may be a pure reaction to being caught on the hook. Our other theory is that the tuna dives down in order to locate the school from its silhouette against the sky. Because over half the fish we have observed so far have swum back into the school within a short space of time.

Once in the school, their behaviour and swimming speed matches that of the other fish. Seemingly they are not greatly affected by being caught on a hook.

These observations have been made using cameras and accelerometers attached to the hook.

“It is not clear whether the fish are experiencing elevated levels of stress during this part of the fight. We need more data to comment on their stress levels, but in any case it is very interesting that they tend to swim normally with the school”, says Breen.

Next, the rod and line fishers who minimise the fight time chase the fish down with their boat. They only start to “fight” when they are directly above the school and the fish.

“Then there is only a short way up. Some fishers spend less than 30 minutes in total landing the fish”, says Michael Breen.

Studying Japanese slaughter methods

One problem with bluefin tuna is that it can “overheat” when it becomes stressed or if it is handled wrong.

This phenomenon, which spoils the meat, is known as yake and mure in Japanese, or “burnt tuna syndrome”. The underlying mechanism is not well documented, but temperature, lactic acid and stress hormones may all be factors. (See fact box)

How quickly the tuna is slaughtered also matters, and the researchers are studying methods that are suitable for small boats. These include the Japanese ikejime technique.

Michelin-starred chef dispels myths

“Many people assume that yake will be prevalent in rod and line caught bluefin tuna, but initial results indicate that quite the opposite is true. Rod and line fishing may be a good way of obtaining restaurant-grade fish”, says Breen.

The first bluefin tuna of the year caught under the WelTuna project ended its days at the Michelin-starred restaurant Lysverket in Bergen.

“This could be the best bluefin tuna we have ever tasted”, says owner an head chef Christopher Haatuft.

“I imagine it is down to the fight time, which I understand was around 20 minutes, rapid slaughter and how it was handled”, he says.

The 2025 fishing season has been very slow for rod and line fishers, including the research team. It is now drawing to a close.

The researchers are planning more trials to obtain more data next year.