Baleen whales have a summer job as ocean fertilizers

Baleen whales often release feces before initiating a deep dive.

Photo: Carla Freitas / The Institute of Marine ResearchPublished: 13.11.2025

Phytoplankton are the “grass of the sea” – and to truly bloom, they need a steady supply of nutrients.

Here, baleen whales play an important role, according to new findings.

Each summer, thousands of baleen whales, such as minke and fin whales, migrate north to feed in Arctic and sub-Arctic waters – and, as it turns out, they also help to fertilize them:

“By recycling nutrients in the ocean, these baleen whales can increase primary production by up to ten percent,” says marine researcher Carla Freitas.

Scientists have long suspected that whales recycle nutrients, but now they have quantified how large their contribution is.

One nutrient mix in the poo, another in urine

Previous research has shown that the 15,000 minke whales feeding around Svalbard defecate about 600 tons per day.

Now, researchers have also analyzed their urine:

“Nitrogen is mainly excreted through urine. Phosphorus and other essential trace metals such as iron, zinc, copper, and manganese are mostly excreted through feces,” explains Freitas.

Both nitrogen, phosphorus and trace metals are key ingredients for phytoplankton – and the lack of these nutrients limits production. Nitrogen is particularly limiting in this region.

“Whale urine is not only a major source of nitrogen – it’s released in a form that phytoplankton can easily use,” Freitas add.

Photo: Carla Freitas / IMR

Up to 10 percent

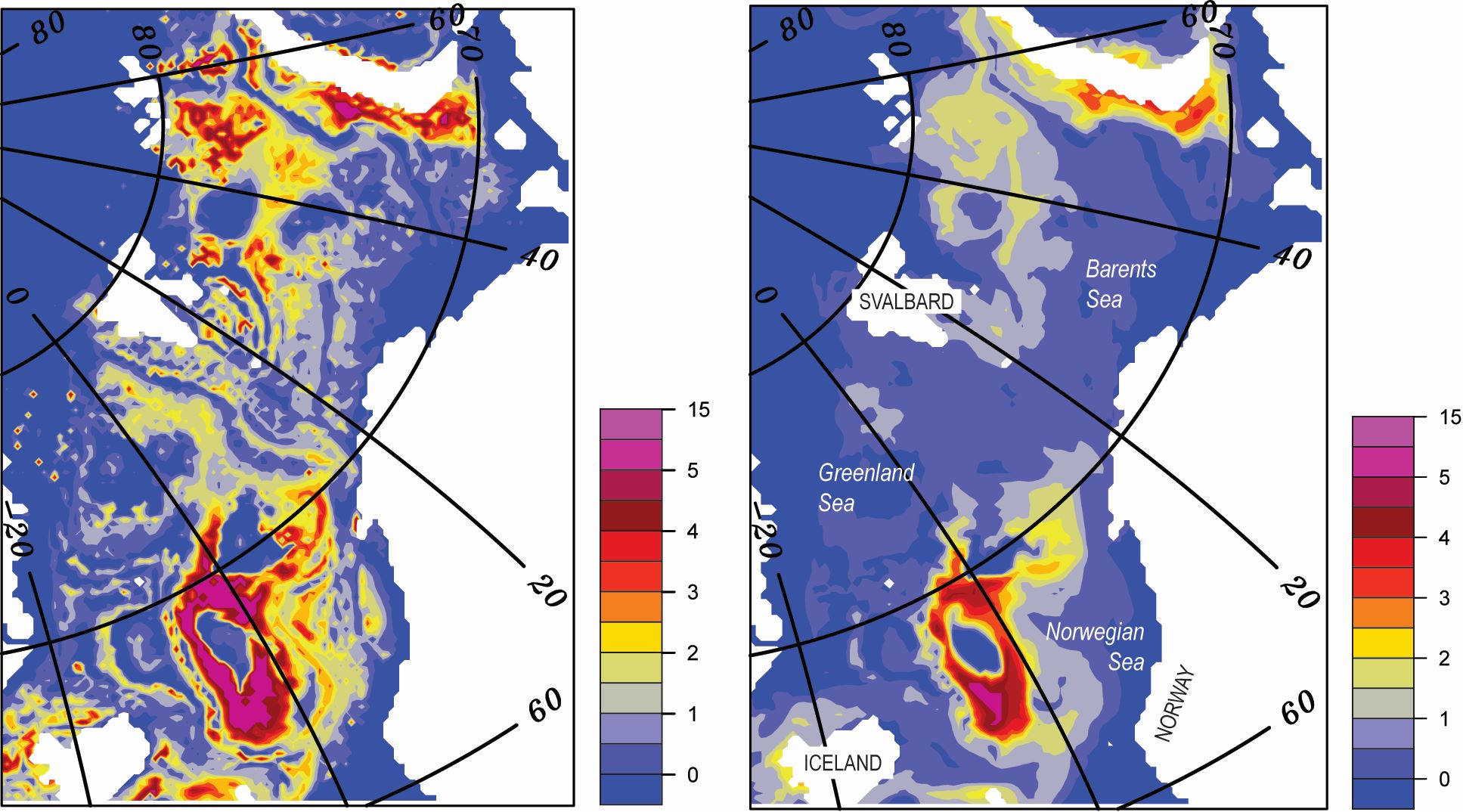

The study focused on baleen whales feeding in the Barents Sea, Norwegian Sea, Greenland Sea, and Iceland Sea.

Baleen whales include minke, fin, sei, humpback, blue, and bowhead whales.

Researchers used an ecosystem model to simulate primary production under two scenarios: one with and one without nutrients from whales.

The contribution varied by time and place.

“We found the greatest effect in summer, when waters are stratified and nutrient levels are low – and in offshore areas far from other nutrient sources,” explains ocean researcher Morten Skogen.

Under such conditions, whale fertilization can boost primary production by up to 10 percent. Annually the effect is smaller – up to four percent.

More than top predators

The study suggests that increased primary production due to whale fertilization has cascading effects throughout the food web – leading to up to 10 percent more zooplankton, which in turn feeds fish and other species.

“Whales are not just top predators – they are key species in the marine food web, recycling nutrients and contributing to a productive ecosystem,” says Carla Freitas.