“Superbugs” may spread from Svalbard

The study shows the consequences human activity has on the Arctic microbiota. This is crucial for understanding environmental impacts in vulnerable Arctic ecosystems.

Photo: Erlend Astad Lorentzen / IMR

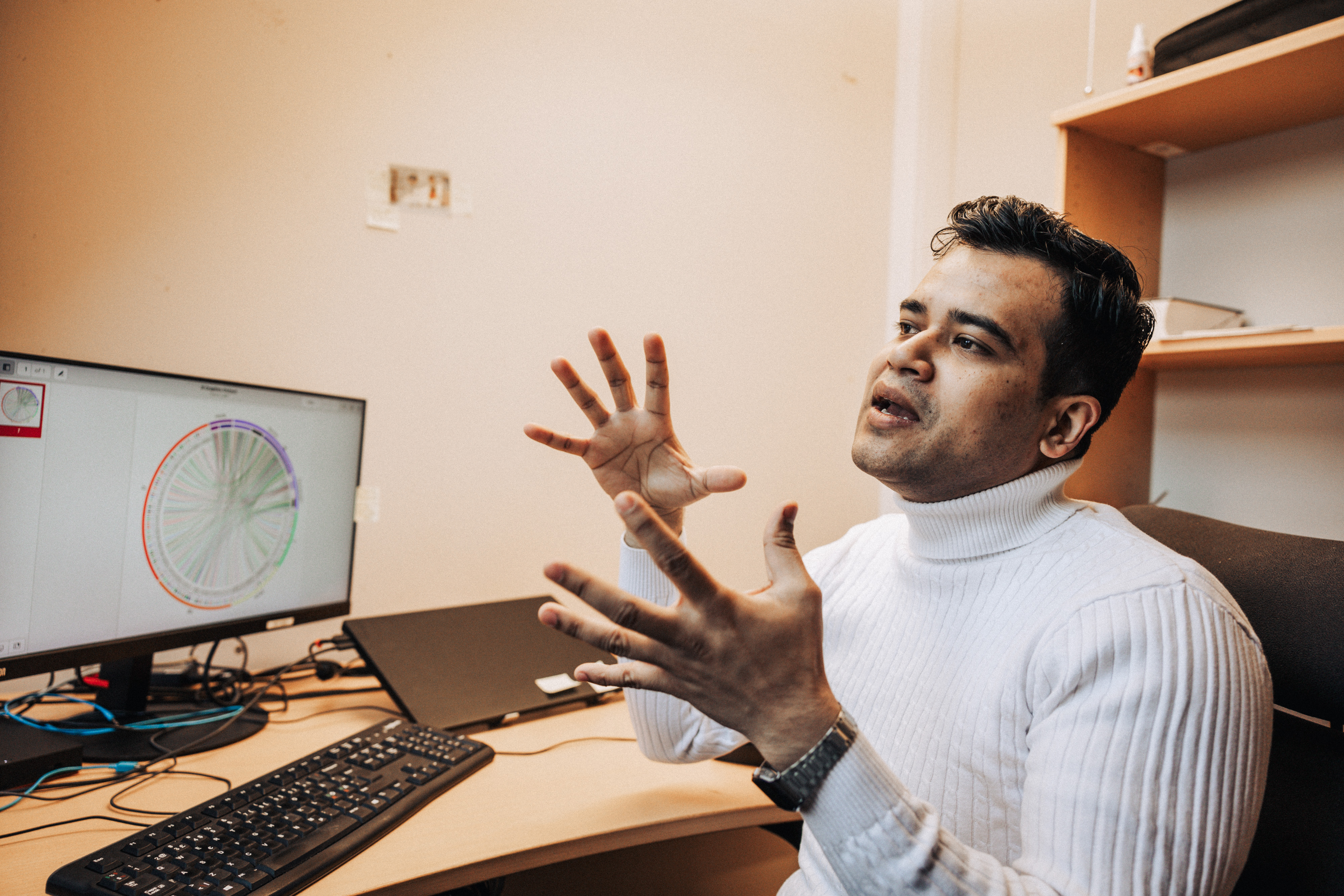

The researchers Nachiket Marathe (left) and Manish Paraksh Victor also compared their data with previous studies from other researchers who studied different parts of the Arctic, such as permafrost and seawater.

Photo: Erlend Astad Lorentzen / IMRPublished: 19.02.2026

“Our study suggests that the Arctic microbial community could become a source for the emergence of ‘superbugs’,” says researcher Manish Prakash Victor.

Marine researchers have investigated the unexplored biodiversity at the bottom of Adventfjorden in Svalbard using eDNA sequencing (metagenomics) and computational models.

The result: hundreds of new bacteria and even more antibiotic-resistant genes.

Foto: Erlend Astad Lorentzen / Havforskingsinstituttet

Exploring a Hidden World

“We knew that Arctic sediments likely harbored a huge diversity of microbes that had never been described before,” says Marathe. He is the project leader and the last author of the study where the new findings are presented.

Between 75 and 95 percent of all biomass in the ocean consists of microbes. These tiny organisms play a crucial role – they are responsible for recycling nutrients.

But large parts of this world remain hidden, unknown, and understudied.

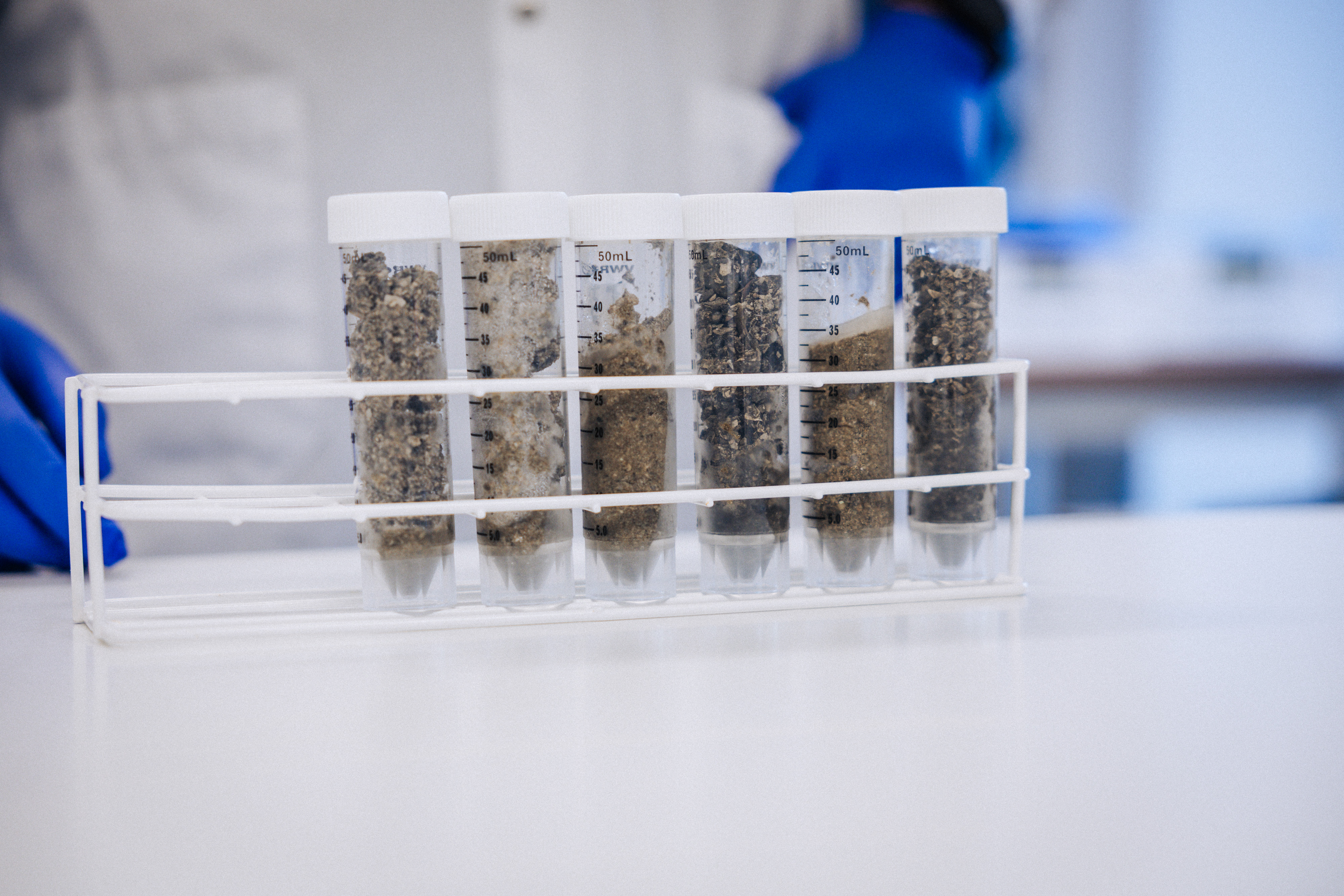

The marine researchers collected sediment samples from nine different locations in Adventfjorden. Back in the lab, they examined what the sediments contained – not only what microbes were present but also what genes they carried.

“We investigated 644 bacterial genomes in the samples. Of these, over 97 percent were new bacteria,” says Marathe. “That says something about the level of unexplored diversity we’re dealing with.”

Foto: Nadja Junghardt (etter avtale)

Human Bacteria in the “Untouched” Arctic

The microbes from the fjord bottom also showed widespread antibiotic resistance.

The researchers found 888 clinically relevant antibiotic-resistant genes in the Svalbard microbes. “Clinically relevant” means that they may affect public health.

“The findings are alarming,” says Marathe.

Some of these genes are resistant to so-called “last-resort” antibiotics like carbapenems, colistin, vancomycin, linezolid, and tigecycline.

These are antibiotics used when more targeted medicines fail and can’t eliminate the infection.

“The fact that we find these antibiotic-resistant genes in the microbial community suggests that there are also human-origin bacteria in Adventfjorden,” says Marathe.

“This is likely due to wastewater being released into the fjord.”

The Arctic as an Antibiotic Resistance Reservoir

That these antibiotic-resistant genes are found in environmental samples is significant, because it suggests that resistance to medically important antibiotics exists outside of clinical settings.

“This could affect how effective these antibiotics are at treating human infections. Our findings show that the Arctic could become a reservoir for antibiotic resistance and potentially contribute to the global spread of antibiotic-resistant diseases.”

Climate change may also play a role as a wild card.

Researchers are concerned that warmer waters and human activities – such as discharging wastewater into the fjord and increasing tourism – could lead to resistance genes being transferred to disease-causing bacteria:

“This could lead to the emergence of ‘superbugs’ carrying new types of antibiotic resistance that are difficult to treat.”

Foto: Erlend Astad Lorentzen / Havforskingsinstituttet

Doubled the Database

At the same time, the researchers discovered 478 new beta-lactam resistance genes, which belong to 217 new families.

Beta-lactams are a group of antibiotics considered particularly effective against bacterial infections.

These were found in samples from Arctic niches, including sediment, seawater, and permafrost. This suggests that beta-lactam resistance genes are widespread and distributed in Arctic environments.

“We’ve nearly doubled the number of families we have in the global database,” says Victor.

This is a major expansion of our knowledge of potential antibiotic resistance mechanisms.

“This may lead to new insights into evolution of antibiotic resistance and potentially contribute to the development of new mitigation strategies to counter spread of resistance,” the researcher says.